Europe’s Last Soviet Economy Approaches Its ‘Hour of Reckoning’

By Marc Champion and Aliaksandr Kudrytski, Bloomberg Businessweek

9 December 2019, 11:50

Belarus kept old factories, jobs, and social services alive after communism. Now that model is under threat from Russia.

Belarus kept old factories, jobs, and social services alive after communism. Now that model is under threat from Russia.

Andrei Suslenkou, director for ideological work at the Minsk Tractor Factory, is proudly showing off the benefits his company offers, at low or no cost, to more than 30,000 workers and retirees. At the plant’s health clinic, 560 doctors and staff use sleek Western equipment to provide care from routine checkups to surgery, including laser eyesight correction. A Palace of Culture opposite the factory’s ornate, Stalin-era gates includes a plush theater wired for light and sound. It just hosted a concert in honor of the “Day of Machine Builders.” Outside the capital, a woodland sanatorium provides cures, vacations, and summer camps for 300 employees’ kids at a time. “They were smart professionals back then who set up these social services,” says Suslenkou, adding that he audited the system Soviet planners made for the factory and found little “excess” to cut.

Call it the Belarus exception. Almost 28 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, this deeply cautious nation of 9.5 million—rolled over through the centuries by Moscow’s wars with other parts of Europe—has kept alive many of the industrial jobs and social ecosystems that centrally planned factory budgets once supported across the bloc.

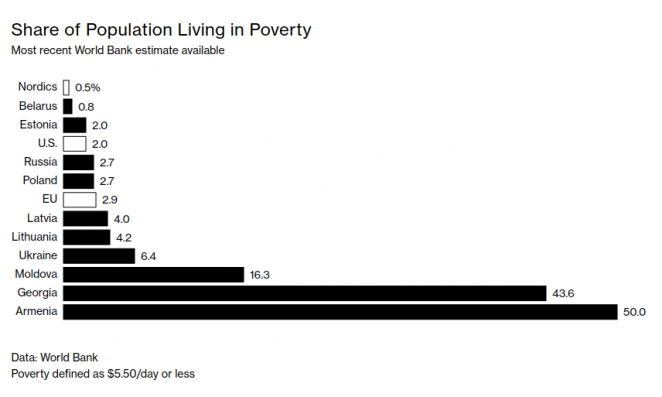

In the West, Belarus is probably best known as “Europe’s last dictatorship.” Less recognized is that its transition from command to semi-market economy, delivered at the speed of a mud-bound tractor, has by some economic measures made this a better place to live than any other former Soviet republic, barring the three Baltic States that joined the European Union. Belarus scores better on inequality than any EU nation (including the likes of Denmark), and has a smaller percentage of people living on less than $5.50 per day, a World Bank measure of poverty, than any other part of what was once the Soviet Union, half of the EU’s 28 member states, or the U.S.

In place of the potholed roads, rundown buildings, and the depopulation found in some other struggling ex-Soviet nations, President Alexander Lukashenko, now 65 and in charge since 1994, has turned Minsk into something of a Soviet theme park. It’s a vision of how he believes things might have been without the communist empire’s 1991 collapse. Statues of Lenin and other Bolshevik heroes still dominate cityscapes. Stalin-era buildings and boulevards are immaculately maintained and painted; parks are manicured and pavements swept clean. After Lukashenko visited the tractor factory in 2015, managers restored communist-era friezes removed during the campaign against “architectural excesses” that followed Stalin’s death, in 1953.

“I think Belarus does have a unique path,” one that has had some under-recognized benefits such as stability, says Alexander Pivovarsky, the EBRD’s country manager, in an interview at his office in central Minsk. “But we believe the economic model of Belarus is unsustainable.”

Indeed, Lukashenko’s exception is now under threat, for the same reason it would be hard for others to emulate: It was made possible by billions of dollars’ worth of de facto annual Russian energy subsidies, in the form of large quantities of crude oil which Belarus buys at a discount. Russia is withdrawing those subsidies through a so-called tax maneuver, which will eliminate an exemption that benefitted Belarus. Its refineries already pay 80% of the world price for Russian oil—up from 50% five years ago—and as a result of the tax change they will pay full price by 2025, at a cost, says the government, of $10 billion over those six years. (Belarus also pays as little as half as much as Western European countries for Russian natural gas. Negotiations to continue that discount are ongoing.)

Without compensation for these lost subsidies, Belarus may have to restructure its legacy state-owned factories, losing many of the jobs and welfare systems they sustain. “What you have to remember is that Belarus is an oil economy. It doesn’t look like an oil exporter, but it is, because all the time it has been getting cheap oil from Russia,” which it then refines for re-export to Europe, says Sergei Guriev, a former chief economist for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. “That’s about to change, and we have this hour of reckoning.”

The Kremlin is making any compensation to soften the blow contingent on a deal to integrate the two countries. That’s forcing Lukashenko to navigate a choice he has long sought to avoid: Cut a deal with Russia, at the risk of being seen to sacrifice sovereignty, or put the nation’s heavy industry on a commercial footing and turn westward for support, risking retribution from Moscow. An agreement resulting from months of intense negotiations is due to be signed on Dec. 8.

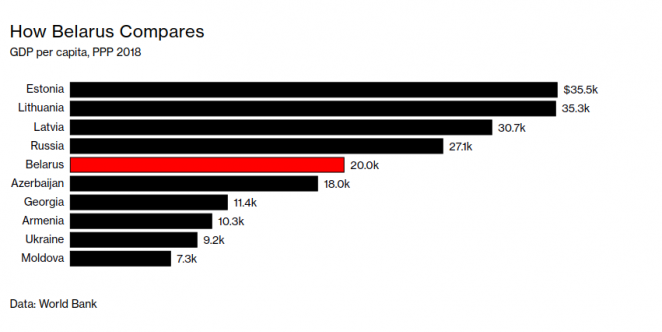

Until now, Lukashenko has managed dealings with Russia in a way that other ex-Republics have been unable to achieve. In part thanks to the resulting stability, Belarus’s per capita gross domestic product is, in U.S. dollar terms, about twice as high as in fellow ex-republics Georgia, Moldova, or Ukraine. Those three countries have experimented more with market economics, democracy, and a pro-European direction, which brought clashes with Moscow. Instead of cheap energy, they got Russian sanctions, political interference, and territorial dismemberment. The price Belarusians have had to pay for that stability, in terms of lost human rights protections and political freedoms, has been exorbitant. The domestic security service is still called the KGB. A 2018 United Nations report cited abuses that ranged from police torture to restrictions on the freedom of expression.

Yet a lot has changed since Belarusians voted in a referendum to keep the Soviet Union intact by a margin of 84% to 16%, shortly before it collapsed in 1991. On coming to power, Lukashenko, a former collective farm director, took advantage of that nostalgia to turn the clock back on liberal reforms made in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse. Among other measures, he abolished some direct local elections, limited the right to buy and sell farmland and restored Russian as an official language. He also moved Independence Day to mark the Soviet liberation of Minsk from Nazi occupation, in 1944, instead of Belarus’s 1990 declaration of sovereignty from the Soviet Union.

He wasn’t shy about his views on private enterprise, either. “In 10 years, I’ll shake the hand of the last entrepreneur,” he said in 1995, according to local media reports. “Entrepreneurs are lousy fleas, there is no need for them!” Four years later, he signed a deal with Russia to merge the two countries’ political and economic institutions to form a partially reunified state that he seemed—in the days before Vladimir Putin took over in Moscow—a viable candidate to head.

Today, Lukashenko pins medals on entrepreneurs’ chests and casts himself as defender of Belarus sovereignty. About 50% of the economy is in private hands. In downtown Minsk, numerous bars, restaurants, and private shops have sprung up among the city’s Stalin-era buildings and the sprinkling of stores that still advertise their wares, Soviet-style, as just “Shoes,” “Books,” or “Groceries.” And for all his reluctance to privatize big, state-owned employers, Lukashenko has used targeted tax breaks and regulatory dispensations to encourage the growth of a vibrant private tech sector. This has helped produce the makers of the global hit video game World of Tanks, as well as IT outsourcing company Epam Systems Inc., listed on the New York Stock Exchange with a market cap of more than $11 billion.

“These are real success stories,’’ says Guriev, now a professor of economics at Sciences Po, the Paris Institute of Political Studies. Still, both tech companies moved their headquarters out of the country as soon as they grew big—Epam to New York and Wargaming Group Ltd. to Cyprus. “Entrepreneurs are not protected from the KGB,” Guriev says.

What made Belarus different from its neighbors was Lukashenko’s refusal to privatize the economy in the 1990s, preventing the emergence of the powerful so-called oligarchs who snapped up vast state assets in Ukraine and Russia, according to Pavel Daneyko, director general of the IPM Business School in Minsk. Rather than acquire Soviet-rooted companies like the Minsk tractor factory, known as MTZ, would-be entrepreneurs in Belarus had to build businesses from scratch in greenfield sectors such as IT and retail. The owner of a chain of supermarkets, Eurotorg LLC, now claims to be the nation’s largest private company by number of employees.

For a long time, Lukashenko’s hostility to private enterprise made that development difficult. “In 2005, the KGB told me to leave the country for a couple of years,” says Daneyko. The business school he ran at the time was being forced to close. “I went to Moscow, and I thought Russia was a kind of paradise for business, compared to Belarus,” he says. With the emergence of a relatively benign, oligarch-free, if limited form of capitalism, Belarus has, according to Daneyko, turned the tables.

Belarusians are no longer as keen as they once were to be ruled from Moscow. A recent opinion survey by the non-government polling agency BAW found that 75.6% of respondents wanted Belarus and Russia to remain independent, friendly states. Even as it tries to limit the coming deal with the Kremlin to economic integration, the government is also trying to sign a trade agreement with the EU and to boost trade and investment ties with China. “Belarus has always acutely sensed the breath of the geopolitical wind,” Foreign Minister Vladimir Makei said, during an October conference in Minsk. “Recently, we have been living under constant storm alert.”

The problem for Belarus is that “while they have achieved the impossible—preserving all the advantages they had—so that they now have a future,” that strategy has left the country dependent on Russia to an extent that trade data underestimate, says Vasily Kashin, a defense specialist and senior research fellow in Moscow’s Higher School of Economics.

For example, MTZ exports more than 90% of the 32,000 tractors it makes every year, with Russia—by far the largest market—buying about a third of them. Belarus’s other big machinery plants are at least as dependent. A quarter of exports to Europe, meanwhile, are petroleum products, dependent on discounted crude coming from Moscow. “Russia could shut them all down within months; the economy would collapse,” says Kashin.

Belarus’s burgeoning tech sector, in part a legacy of the country’s specialization in producing the electronics at the smart end of the Soviet military machine, is far less Russia-dependent. The government offers tax and regulatory relief to companies accepted into a virtual Hi-Tech Park; that help is essential precisely because the competition is global and comes from the likes of India, as well as Russia, Europe, and the U.S., says Yury Pliashkou, founder and chief executive of IdeaSoft, a small IT outsourcing company in Minsk.

Tech, however, isn’t enough. The economy as a whole has grown at a snail’s pace since the global financial crisis (an average 1.7% per annum since 2009, compared to 7.5% over the previous decade). According to one estimate, that slide has coincided with a drop in Russian energy subsidies to between 5% and 10% of Belarus’s GDP, from a pre-crisis high of 20% of GDP. A top official at state oil company Belneftekhim said at the end of October that Belarus refineries lost $250 million over the first nine months of this year, a result of the latest changes to Russia’s tax code.

The government has been racking up debt to keep its economic model afloat. The economy has also begun to look less egalitarian, with wealth concentrating in tech-heavy Minsk as most other regions fall behind. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that unless Lukashenko can secure compensation from Moscow, the change to Russia’s tax rules for its energy companies will cost the country a further 5.2% of its annual $60 billion GDP by 2023. The solution, according to the fund: Either restructure, privatize, or close those big, legacy Soviet factories to cut government spending on subsidies, much as was done elsewhere during the 1990s.

“We are moving to liberalize, but gradually, we are not going to do it in a shock manner,” says Anatoly Glaz, spokesman for the foreign ministry. “You see the situation in a number of countries, including those near us; social stability is important to us.” Glaz also pushed back against the whole concept of Russian subsidies, arguing that Moscow is obliged to sell energy to Belarusian companies at the same price as to Russian ones under the integrated market rules of the Eurasian Economic Union, to which both countries belong. “It is not a subsidy, it is a question of equality, of equal prices. They can even be world prices, but they must be the same, otherwise we cannot compete in the same market.”

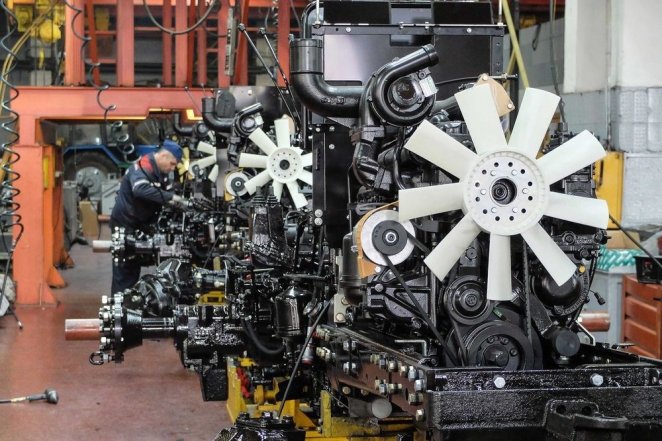

On the production line back at MTZ, workers currently assemble 120 models and modifications of tractors, up from four in the Soviet days, from tiny 8-horsepower machines to 350-horsepower, computer aided monsters that can cost upward of $120,000. Computers allocate the required parts and operate the 14 kilometers (8.7 miles) of conveyor belts that supply production lines. It’s a commercial operation now, says Suslenkou, as paying tourists file into the main production hall before moving on to a gut-wrenching, strap-in tractor race simulator and finally, a gift shop selling everything from toy tractors to a branded ax. As for worker benefits, “we’ve noticed that the companies that closed their social services are the ones that are now having trouble retaining workers,” he says. The medical clinic alone costs MTZ $4 million a year to run, according to its chief doctor.

Published annual accounts suggest MTZ turns a profit. If that’s accurate, it’s likely thanks to a basic $12,000-$14,000 tractor model that remains popular across the former Soviet Union, Africa, and Asia because it’s inexpensive and simple enough for farmers to fix themselves. Others among Belarus’s legacy industries have struggled harder to keep markets or find new ones.

Daneyko, the business school director, was recently hired to advise on a turnaround plan for one of these, the state-owned combine harvester maker OSJC Gomselmash. Restructuring such ex-Soviet behemoths, he says, will inevitably lead to privatization. And with that could come the end of Lukashenko’s post-Soviet dream.

9 December 2019, 11:50

Inside the production facilities at MTZ. PHOTOGRAPHER: MARC CHAMPION/BLOOMBERG

Andrei Suslenkou, director for ideological work at the Minsk Tractor Factory, is proudly showing off the benefits his company offers, at low or no cost, to more than 30,000 workers and retirees. At the plant’s health clinic, 560 doctors and staff use sleek Western equipment to provide care from routine checkups to surgery, including laser eyesight correction. A Palace of Culture opposite the factory’s ornate, Stalin-era gates includes a plush theater wired for light and sound. It just hosted a concert in honor of the “Day of Machine Builders.” Outside the capital, a woodland sanatorium provides cures, vacations, and summer camps for 300 employees’ kids at a time. “They were smart professionals back then who set up these social services,” says Suslenkou, adding that he audited the system Soviet planners made for the factory and found little “excess” to cut.

Call it the Belarus exception. Almost 28 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, this deeply cautious nation of 9.5 million—rolled over through the centuries by Moscow’s wars with other parts of Europe—has kept alive many of the industrial jobs and social ecosystems that centrally planned factory budgets once supported across the bloc.

In the West, Belarus is probably best known as “Europe’s last dictatorship.” Less recognized is that its transition from command to semi-market economy, delivered at the speed of a mud-bound tractor, has by some economic measures made this a better place to live than any other former Soviet republic, barring the three Baltic States that joined the European Union. Belarus scores better on inequality than any EU nation (including the likes of Denmark), and has a smaller percentage of people living on less than $5.50 per day, a World Bank measure of poverty, than any other part of what was once the Soviet Union, half of the EU’s 28 member states, or the U.S.

In place of the potholed roads, rundown buildings, and the depopulation found in some other struggling ex-Soviet nations, President Alexander Lukashenko, now 65 and in charge since 1994, has turned Minsk into something of a Soviet theme park. It’s a vision of how he believes things might have been without the communist empire’s 1991 collapse. Statues of Lenin and other Bolshevik heroes still dominate cityscapes. Stalin-era buildings and boulevards are immaculately maintained and painted; parks are manicured and pavements swept clean. After Lukashenko visited the tractor factory in 2015, managers restored communist-era friezes removed during the campaign against “architectural excesses” that followed Stalin’s death, in 1953.

MTZ’s main building.PHOTOGRAPHER: ALIAKSANDR KUDRYTSKI/BLOOMBERG

“I think Belarus does have a unique path,” one that has had some under-recognized benefits such as stability, says Alexander Pivovarsky, the EBRD’s country manager, in an interview at his office in central Minsk. “But we believe the economic model of Belarus is unsustainable.”

Indeed, Lukashenko’s exception is now under threat, for the same reason it would be hard for others to emulate: It was made possible by billions of dollars’ worth of de facto annual Russian energy subsidies, in the form of large quantities of crude oil which Belarus buys at a discount. Russia is withdrawing those subsidies through a so-called tax maneuver, which will eliminate an exemption that benefitted Belarus. Its refineries already pay 80% of the world price for Russian oil—up from 50% five years ago—and as a result of the tax change they will pay full price by 2025, at a cost, says the government, of $10 billion over those six years. (Belarus also pays as little as half as much as Western European countries for Russian natural gas. Negotiations to continue that discount are ongoing.)

Without compensation for these lost subsidies, Belarus may have to restructure its legacy state-owned factories, losing many of the jobs and welfare systems they sustain. “What you have to remember is that Belarus is an oil economy. It doesn’t look like an oil exporter, but it is, because all the time it has been getting cheap oil from Russia,” which it then refines for re-export to Europe, says Sergei Guriev, a former chief economist for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. “That’s about to change, and we have this hour of reckoning.”

The Kremlin is making any compensation to soften the blow contingent on a deal to integrate the two countries. That’s forcing Lukashenko to navigate a choice he has long sought to avoid: Cut a deal with Russia, at the risk of being seen to sacrifice sovereignty, or put the nation’s heavy industry on a commercial footing and turn westward for support, risking retribution from Moscow. An agreement resulting from months of intense negotiations is due to be signed on Dec. 8.

Until now, Lukashenko has managed dealings with Russia in a way that other ex-Republics have been unable to achieve. In part thanks to the resulting stability, Belarus’s per capita gross domestic product is, in U.S. dollar terms, about twice as high as in fellow ex-republics Georgia, Moldova, or Ukraine. Those three countries have experimented more with market economics, democracy, and a pro-European direction, which brought clashes with Moscow. Instead of cheap energy, they got Russian sanctions, political interference, and territorial dismemberment. The price Belarusians have had to pay for that stability, in terms of lost human rights protections and political freedoms, has been exorbitant. The domestic security service is still called the KGB. A 2018 United Nations report cited abuses that ranged from police torture to restrictions on the freedom of expression.

Yet a lot has changed since Belarusians voted in a referendum to keep the Soviet Union intact by a margin of 84% to 16%, shortly before it collapsed in 1991. On coming to power, Lukashenko, a former collective farm director, took advantage of that nostalgia to turn the clock back on liberal reforms made in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse. Among other measures, he abolished some direct local elections, limited the right to buy and sell farmland and restored Russian as an official language. He also moved Independence Day to mark the Soviet liberation of Minsk from Nazi occupation, in 1944, instead of Belarus’s 1990 declaration of sovereignty from the Soviet Union.

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko after a meeting of the CIS Heads of State Council, on Oct. 11, 2019.PHOTOGRAPHER: MIKHAIL METZEL/TASS/GETTY IMAGES

He wasn’t shy about his views on private enterprise, either. “In 10 years, I’ll shake the hand of the last entrepreneur,” he said in 1995, according to local media reports. “Entrepreneurs are lousy fleas, there is no need for them!” Four years later, he signed a deal with Russia to merge the two countries’ political and economic institutions to form a partially reunified state that he seemed—in the days before Vladimir Putin took over in Moscow—a viable candidate to head.

Today, Lukashenko pins medals on entrepreneurs’ chests and casts himself as defender of Belarus sovereignty. About 50% of the economy is in private hands. In downtown Minsk, numerous bars, restaurants, and private shops have sprung up among the city’s Stalin-era buildings and the sprinkling of stores that still advertise their wares, Soviet-style, as just “Shoes,” “Books,” or “Groceries.” And for all his reluctance to privatize big, state-owned employers, Lukashenko has used targeted tax breaks and regulatory dispensations to encourage the growth of a vibrant private tech sector. This has helped produce the makers of the global hit video game World of Tanks, as well as IT outsourcing company Epam Systems Inc., listed on the New York Stock Exchange with a market cap of more than $11 billion.

“These are real success stories,’’ says Guriev, now a professor of economics at Sciences Po, the Paris Institute of Political Studies. Still, both tech companies moved their headquarters out of the country as soon as they grew big—Epam to New York and Wargaming Group Ltd. to Cyprus. “Entrepreneurs are not protected from the KGB,” Guriev says.

What made Belarus different from its neighbors was Lukashenko’s refusal to privatize the economy in the 1990s, preventing the emergence of the powerful so-called oligarchs who snapped up vast state assets in Ukraine and Russia, according to Pavel Daneyko, director general of the IPM Business School in Minsk. Rather than acquire Soviet-rooted companies like the Minsk tractor factory, known as MTZ, would-be entrepreneurs in Belarus had to build businesses from scratch in greenfield sectors such as IT and retail. The owner of a chain of supermarkets, Eurotorg LLC, now claims to be the nation’s largest private company by number of employees.

Inside the MTZ tractor factory.PHOTOGRAPHER: MARC CHAMPION/BLOOMBERG

For a long time, Lukashenko’s hostility to private enterprise made that development difficult. “In 2005, the KGB told me to leave the country for a couple of years,” says Daneyko. The business school he ran at the time was being forced to close. “I went to Moscow, and I thought Russia was a kind of paradise for business, compared to Belarus,” he says. With the emergence of a relatively benign, oligarch-free, if limited form of capitalism, Belarus has, according to Daneyko, turned the tables.

Belarusians are no longer as keen as they once were to be ruled from Moscow. A recent opinion survey by the non-government polling agency BAW found that 75.6% of respondents wanted Belarus and Russia to remain independent, friendly states. Even as it tries to limit the coming deal with the Kremlin to economic integration, the government is also trying to sign a trade agreement with the EU and to boost trade and investment ties with China. “Belarus has always acutely sensed the breath of the geopolitical wind,” Foreign Minister Vladimir Makei said, during an October conference in Minsk. “Recently, we have been living under constant storm alert.”

The problem for Belarus is that “while they have achieved the impossible—preserving all the advantages they had—so that they now have a future,” that strategy has left the country dependent on Russia to an extent that trade data underestimate, says Vasily Kashin, a defense specialist and senior research fellow in Moscow’s Higher School of Economics.

For example, MTZ exports more than 90% of the 32,000 tractors it makes every year, with Russia—by far the largest market—buying about a third of them. Belarus’s other big machinery plants are at least as dependent. A quarter of exports to Europe, meanwhile, are petroleum products, dependent on discounted crude coming from Moscow. “Russia could shut them all down within months; the economy would collapse,” says Kashin.

Assembly line at MTZ.PHOTOGRAPHER: MARC CHAMPION/BLOOMBERG

Belarus’s burgeoning tech sector, in part a legacy of the country’s specialization in producing the electronics at the smart end of the Soviet military machine, is far less Russia-dependent. The government offers tax and regulatory relief to companies accepted into a virtual Hi-Tech Park; that help is essential precisely because the competition is global and comes from the likes of India, as well as Russia, Europe, and the U.S., says Yury Pliashkou, founder and chief executive of IdeaSoft, a small IT outsourcing company in Minsk.

Tech, however, isn’t enough. The economy as a whole has grown at a snail’s pace since the global financial crisis (an average 1.7% per annum since 2009, compared to 7.5% over the previous decade). According to one estimate, that slide has coincided with a drop in Russian energy subsidies to between 5% and 10% of Belarus’s GDP, from a pre-crisis high of 20% of GDP. A top official at state oil company Belneftekhim said at the end of October that Belarus refineries lost $250 million over the first nine months of this year, a result of the latest changes to Russia’s tax code.

The government has been racking up debt to keep its economic model afloat. The economy has also begun to look less egalitarian, with wealth concentrating in tech-heavy Minsk as most other regions fall behind. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that unless Lukashenko can secure compensation from Moscow, the change to Russia’s tax rules for its energy companies will cost the country a further 5.2% of its annual $60 billion GDP by 2023. The solution, according to the fund: Either restructure, privatize, or close those big, legacy Soviet factories to cut government spending on subsidies, much as was done elsewhere during the 1990s.

“We are moving to liberalize, but gradually, we are not going to do it in a shock manner,” says Anatoly Glaz, spokesman for the foreign ministry. “You see the situation in a number of countries, including those near us; social stability is important to us.” Glaz also pushed back against the whole concept of Russian subsidies, arguing that Moscow is obliged to sell energy to Belarusian companies at the same price as to Russian ones under the integrated market rules of the Eurasian Economic Union, to which both countries belong. “It is not a subsidy, it is a question of equality, of equal prices. They can even be world prices, but they must be the same, otherwise we cannot compete in the same market.”

A sign for Minsk Tractor Works in Belarus.PHOTOGRAPHER: MARC CHAMPION/BLOOMBERG

On the production line back at MTZ, workers currently assemble 120 models and modifications of tractors, up from four in the Soviet days, from tiny 8-horsepower machines to 350-horsepower, computer aided monsters that can cost upward of $120,000. Computers allocate the required parts and operate the 14 kilometers (8.7 miles) of conveyor belts that supply production lines. It’s a commercial operation now, says Suslenkou, as paying tourists file into the main production hall before moving on to a gut-wrenching, strap-in tractor race simulator and finally, a gift shop selling everything from toy tractors to a branded ax. As for worker benefits, “we’ve noticed that the companies that closed their social services are the ones that are now having trouble retaining workers,” he says. The medical clinic alone costs MTZ $4 million a year to run, according to its chief doctor.

Published annual accounts suggest MTZ turns a profit. If that’s accurate, it’s likely thanks to a basic $12,000-$14,000 tractor model that remains popular across the former Soviet Union, Africa, and Asia because it’s inexpensive and simple enough for farmers to fix themselves. Others among Belarus’s legacy industries have struggled harder to keep markets or find new ones.

Daneyko, the business school director, was recently hired to advise on a turnaround plan for one of these, the state-owned combine harvester maker OSJC Gomselmash. Restructuring such ex-Soviet behemoths, he says, will inevitably lead to privatization. And with that could come the end of Lukashenko’s post-Soviet dream.