Is China Cooling On Belarus's Lukashenka?

Reid Standish, Rferl

9 March 2021, 14:08

When Alyaksandr Lukashenka met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi on February 22 to discuss financial and integration issues, there was one political card noticeably absent from the Belarusian leader's hand: China.

When Alyaksandr Lukashenka met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi on February 22 to discuss financial and integration issues, there was one political card noticeably absent from the Belarusian leader's hand: China.

During his 26 years in power, Lukashenka balanced and exploited differences between the West and Russia to strengthen his position at home.

In recent years, China has become another key element -- and an increasingly important economic player -- of the Belarusian leader's geopolitical equation, navigating between Brussels, Moscow, and Beijing to leverage strategic gains and secure much needed loans and investment.

But the ongoing human rights crisis in Belarus, set off by Lukashenka's brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters following the August presidential election that the opposition and international observers have deemed fraudulent, has left Minsk sanctioned by the West and the country's economy increasingly weakened.

Cut off politically from Europe and embattled at home, the strongman has become a far less appealing partner for Beijing.

"Belarus could previously get some money from the West and Russia, and then pivot to China," Katia Glod, a fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, told RFE/RL. "But waning Chinese support means that Minsk has far less space to maneuver, especially with Russia."

Despite the ongoing protests and mass arrests in Belarus that have further tattered Lukashenka's legitimacy at home and abroad, his hold on power remains firm.

In the face of continued calls to step down from opposition leader Svyatlana Tsikhanouskaya -- who lives outside the country but is viewed by many as the actual winner of the presidential election -- Lukashenka said on March 2 that there will be "no transfer of power" in Belarus.

And China's interest in backing the autocrat continues to cool.

While Chinese President Xi Jinping was the first foreign leader to congratulate Lukashenka as the winner of the presidential election in August, Beijing has held back strong economic or political support for Minsk.

China -- which had been a very active investor in Belarus -- has not offered a new project or loan to Minsk since 2019 and is seemingly stepping away from the country's domestic crisis.

That has hurt Lukashenka's leverage as he looks to secure a financial lifeline from Moscow in the face of mounting geopolitical pressure.

China sharply increased its foreign economic footprint around the world in the last decade through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Xi's signature project.

And as the BRI steadily built influence for Beijing through infrastructure, energy, and technology investments, the countries of the former Soviet Union became a testing ground for Chinese policies.

In many ways, Minsk courted Beijing, especially as it faced the pressure of European Union sanctions and tensions with Moscow over control of oil supplies in the 2000s.

But it wasn't until Moscow's annexation of Crimea in 2014 that Belarus became a focal point for China.

Prior to that, Beijing viewed Ukraine as a strategic stepping stone for China to connect itself to the EU. Prior to Russia's illegal annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula, China was engaged in a $10 billion project to build a deep-water port in Crimea that would seek to redistribute cargo flows from Asia to Europe.

Protests in the winter of 2014 that eventually saw the ouster of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych and the outbreak of war in eastern Ukraine, led to China turning its attention more firmly toward Belarus, which positioned itself as an important launching pad on the EU's doorstep for BRI.

In recent years, Chinese money has financed new roads, factories, and rail links with Europe, along with a sprawling industrial park on the outskirts of Minsk that has drawn more than $1 billion in investment from 56 foreign companies, including Chinese technology giants Huawei and ZTE.

Beijing also opened up a $15 billion line of credit to the Development Bank of the Republic of Belarus in 2019 and offered a $500 million loan that same year after Moscow withdrew a similar offer amid tense integration talks.

"China wants stability, that's always the most important thing for Beijing," Peter Braga, an expert on Belarus-China relations at University College London, told RFE/RL.

But Minsk's growing international isolation, especially Lukashenka's falling out with the West, has limited Belarus's strategic value to China.

Braga said Beijing has always viewed Belarus as a risky investment and while China has grown its presence significantly over the years, it has moved cautiously in structuring its loans and deals in the country to limit its own exposure.

Beijing has offered conditional investments with Minsk, pushing Belarus to pour its own money into developments, and also often issued "tied" loans that require Belarusian companies to buy Chinese supplies and tech for Beijing-funded projects in the country.

Moreover, many ventures that China has invested in and issued loans for remain incomplete and behind schedule, making it hesitant to keep adding to Belarus's balance sheet.

Amid the country's ongoing domestic crisis, those concerns have only been amplified and left Beijing to reassess the depth of its commitment to Minsk.

Alyaksandr Lukashenka talks to medical workers during a visit to a district hospital in Stolbtsy on December 8. Even before the election in August, his handling of the coronavirus pandemic angered many in Belarus.

"China will keep up appearances, but that deep relationship is currently on ice," said Braga. "Beijing will only start putting money back in Belarus on a scale like before if Minsk can normalize its relations with Europe."

Despite Chinese uncertainty, Lukashenka has continued to try to attract more Chinese funds into his country.

Speaking at the Belarusian People's Congress in Minsk on February 11, the Belarusian leader pressed for more Chinese companies and banks to become involved in the country, while praising Chinese policy and support.

But with few opportunities for international borrowing and an economy hit by sanctions, the Kremlin -- long Minsk's largest creditor -- remains one of Belarus's few remaining lifelines.

In September, Putin pledged a $1.5 billion loan to Belarus, although the majority of that money will go toward refinancing Minsk's existing debt to Moscow.

Ahead of the February meeting in Sochi, the Russian newspaper Kommersant cited government sources saying that a $3 billion loan would be discussed during Lukashenka's meeting with Putin, although the Belarusian leader later denied this.

Russia has previously made it clear that further economic aid to Belarus is contingent on Minsk accepting greater political integration between the two countries -- a prospect he has long resisted -- and what sort of concessions the Kremlin will push now that Lukashenka has limited outside leverage remains to be seen.

"Belarus would have liked it to be different," said Glod. "But the current political crisis means that Lukashenka no longer has this China card to play."

9 March 2021, 14:08

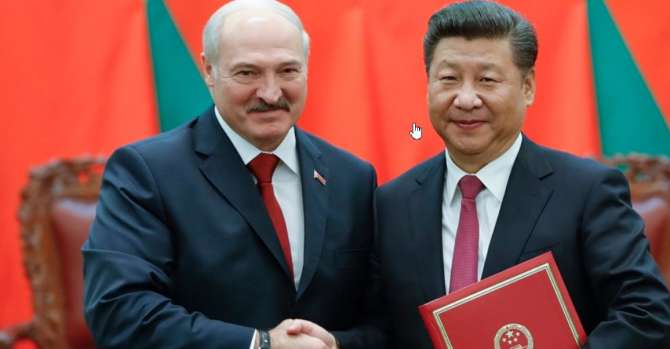

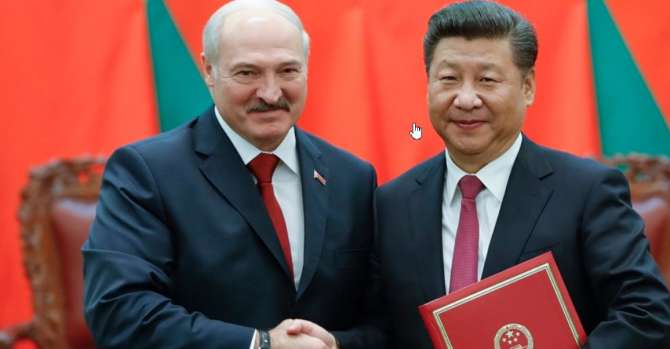

Chinese President Xi Jinping (right) shakes hands with Alyaksandr Lukashenka at a signing ceremony during the Belarusian leader's visit to Beijing in 2016.

During his 26 years in power, Lukashenka balanced and exploited differences between the West and Russia to strengthen his position at home.

In recent years, China has become another key element -- and an increasingly important economic player -- of the Belarusian leader's geopolitical equation, navigating between Brussels, Moscow, and Beijing to leverage strategic gains and secure much needed loans and investment.

But the ongoing human rights crisis in Belarus, set off by Lukashenka's brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters following the August presidential election that the opposition and international observers have deemed fraudulent, has left Minsk sanctioned by the West and the country's economy increasingly weakened.

Far Less Appealing

Cut off politically from Europe and embattled at home, the strongman has become a far less appealing partner for Beijing.

"Belarus could previously get some money from the West and Russia, and then pivot to China," Katia Glod, a fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, told RFE/RL. "But waning Chinese support means that Minsk has far less space to maneuver, especially with Russia."

Despite the ongoing protests and mass arrests in Belarus that have further tattered Lukashenka's legitimacy at home and abroad, his hold on power remains firm.

In the face of continued calls to step down from opposition leader Svyatlana Tsikhanouskaya -- who lives outside the country but is viewed by many as the actual winner of the presidential election -- Lukashenka said on March 2 that there will be "no transfer of power" in Belarus.

And China's interest in backing the autocrat continues to cool.

While Chinese President Xi Jinping was the first foreign leader to congratulate Lukashenka as the winner of the presidential election in August, Beijing has held back strong economic or political support for Minsk.

China -- which had been a very active investor in Belarus -- has not offered a new project or loan to Minsk since 2019 and is seemingly stepping away from the country's domestic crisis.

That has hurt Lukashenka's leverage as he looks to secure a financial lifeline from Moscow in the face of mounting geopolitical pressure.

China's Testing Ground

China sharply increased its foreign economic footprint around the world in the last decade through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Xi's signature project.

And as the BRI steadily built influence for Beijing through infrastructure, energy, and technology investments, the countries of the former Soviet Union became a testing ground for Chinese policies.

Xi Jinping with Alyaksandr Lukashenka during a visit to a China-Belarus industrial park near Minsk in 2015.

In many ways, Minsk courted Beijing, especially as it faced the pressure of European Union sanctions and tensions with Moscow over control of oil supplies in the 2000s.

But it wasn't until Moscow's annexation of Crimea in 2014 that Belarus became a focal point for China.

Prior to that, Beijing viewed Ukraine as a strategic stepping stone for China to connect itself to the EU. Prior to Russia's illegal annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula, China was engaged in a $10 billion project to build a deep-water port in Crimea that would seek to redistribute cargo flows from Asia to Europe.

Protests in the winter of 2014 that eventually saw the ouster of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych and the outbreak of war in eastern Ukraine, led to China turning its attention more firmly toward Belarus, which positioned itself as an important launching pad on the EU's doorstep for BRI.

In recent years, Chinese money has financed new roads, factories, and rail links with Europe, along with a sprawling industrial park on the outskirts of Minsk that has drawn more than $1 billion in investment from 56 foreign companies, including Chinese technology giants Huawei and ZTE.

Beijing also opened up a $15 billion line of credit to the Development Bank of the Republic of Belarus in 2019 and offered a $500 million loan that same year after Moscow withdrew a similar offer amid tense integration talks.

"China wants stability, that's always the most important thing for Beijing," Peter Braga, an expert on Belarus-China relations at University College London, told RFE/RL.

Strategic Value?

But Minsk's growing international isolation, especially Lukashenka's falling out with the West, has limited Belarus's strategic value to China.

Braga said Beijing has always viewed Belarus as a risky investment and while China has grown its presence significantly over the years, it has moved cautiously in structuring its loans and deals in the country to limit its own exposure.

Beijing has offered conditional investments with Minsk, pushing Belarus to pour its own money into developments, and also often issued "tied" loans that require Belarusian companies to buy Chinese supplies and tech for Beijing-funded projects in the country.

Moreover, many ventures that China has invested in and issued loans for remain incomplete and behind schedule, making it hesitant to keep adding to Belarus's balance sheet.

Amid the country's ongoing domestic crisis, those concerns have only been amplified and left Beijing to reassess the depth of its commitment to Minsk.

Alyaksandr Lukashenka talks to medical workers during a visit to a district hospital in Stolbtsy on December 8. Even before the election in August, his handling of the coronavirus pandemic angered many in Belarus.

"China will keep up appearances, but that deep relationship is currently on ice," said Braga. "Beijing will only start putting money back in Belarus on a scale like before if Minsk can normalize its relations with Europe."

All Roads Lead To Moscow

Despite Chinese uncertainty, Lukashenka has continued to try to attract more Chinese funds into his country.

Speaking at the Belarusian People's Congress in Minsk on February 11, the Belarusian leader pressed for more Chinese companies and banks to become involved in the country, while praising Chinese policy and support.

But with few opportunities for international borrowing and an economy hit by sanctions, the Kremlin -- long Minsk's largest creditor -- remains one of Belarus's few remaining lifelines.

Alyaksandr Lukashenka meets with Russian President Vladimir Putin (right) in Sochi in September 2020.

In September, Putin pledged a $1.5 billion loan to Belarus, although the majority of that money will go toward refinancing Minsk's existing debt to Moscow.

Ahead of the February meeting in Sochi, the Russian newspaper Kommersant cited government sources saying that a $3 billion loan would be discussed during Lukashenka's meeting with Putin, although the Belarusian leader later denied this.

Russia has previously made it clear that further economic aid to Belarus is contingent on Minsk accepting greater political integration between the two countries -- a prospect he has long resisted -- and what sort of concessions the Kremlin will push now that Lukashenka has limited outside leverage remains to be seen.

"Belarus would have liked it to be different," said Glod. "But the current political crisis means that Lukashenka no longer has this China card to play."