We Are The Witnesses: Sories From Protesters In Belarus Of Police Torture And Abuse

Rferl

29 August 2020, 00:34

Since the brutal crackdown began against protests disputing the results of the Belarusian presidential election on August 9, which are widely seen as falsified, many have come forward to tell horrific tales of torture and abuse at the hands of the country's security forces.

Since the brutal crackdown began against protests disputing the results of the Belarusian presidential election on August 9, which are widely seen as falsified, many have come forward to tell horrific tales of torture and abuse at the hands of the country's security forces.

RFE/RL's Belarus Service collected the testimonies of people who say they were victims of state-sanctioned violence on the streets and in the jails.

“We agreed to keep quiet to preserve enough air for everybody.”

Yana, a cultural worker, was detained while trying to come to the rescue of a friend. The police van they put her in was packed. She was taken to Akrestsina jail in Minsk and put into a tiny cell designed for six but filled with some 50 detainees. She was tried within the jail walls and got a four-day sentence.

“In my cell, there was an English-language teacher, a mother of five, a designer. We weren’t fed. You could drink from the faucet, but the water was undrinkable. We managed to avoid it for 24 hours but then started to drink. We tried to sleep as best as we could manage. There was no air. We agreed to keep quiet in order to preserve enough air for everybody [to breathe].”

“The men were out for beatings, mostly at night, [perhaps] so no one would hear. But you could hear everything, even the [protest] supporters outside. Workers at the Zhodzina jail cried when we told them our stories [about Akrestsina]. There, we were fed for the first time in three days. Upon leaving, I was presented with a bill for the food given to us at Zhodzina jail.”

![We Are The Witnesses: Sories From Protesters In Belarus Of Police Torture And Abuse]()

“I was released on Thursday night and started to look for my things. We were told that those who came from 'Auschwitz' (Akrestsina jail) would find none of their belongings. There was a feeling that we were deprived of all our rights, that they could do with you whatever they pleased. On the third day, I became hysterical. I started to imagine that I would remain there forever.”

“I asked the police how to get home. In response, they started beating me.”

Hanna, a 30-year-old graphic designer, says she was heading home around midnight on August 11. There was a roadblock, so she asked some police officers how to get around it. They offered to escort her and also asked for identification. Instead of taking her home, they drove to a location where police vans were parked. Suddenly, she was thrown into one of them, and she said they started to beat her.

“They kicked me, beat me with truncheons, with one blow over the head. A large hematoma immediately bloomed on my forehead. They were screaming that I was a coordinator of the protests. They demanded that I admit it and tell them who was paying me. I said I didn’t know what they were talking about. For every response like that, I received another blow. It was the scariest night of my life.”

Hanna recounts that she was then taken to a police precinct building where about 40 people were kept in a large room. Blood and vomit covered the floors. They threw her on the floor and threatened to cut off her dreadlocks. She was then taken to an interrogation room and questioned by seven police officers who kept asking her the same question: Who was financing her "subversive activity?” She said that every time she pleaded ignorance, she was struck with a truncheon below the waist. After that, she was taken into another large room with many people. A police officer came over and spray-painted a number on her shirt. She later found out that the number branded her as one of the protests' most active participants.

The next morning, she was transported to the Akrestsina jail. Lightly dressed in a T-shirt and shorts, she spent the night with two other women in a cold, roofless, cement cell. She says they could hear the screams and moans of men being beaten all night in nearby cells. The following day, she was placed in a cell designed for four, but packed with some 30 or 40 others. Some there hadn’t eaten for two days. One woman arrested with her husband pleaded desperately with the jailers to allow her to telephone her children, who had been left alone at home. On the third day after Hanna's detention, she was released and required to sign a written warning saying that if she were arrested again, she would face criminal charges.

“In the Partyzanski district Internal Affairs Department, we were forced to sing the Belarusian national anthem on our knees while being beaten with truncheons.”

Kiryl, a 21-year-old store clerk, said he was walking to work from a session at the gym on August 12. A bus with tinted windows pulled up and he was ordered to get in. His phone was taken, and he was struck on the head a few times. The bus pulled up to a police van, and he was thrown on the floor. A police officer started to kick him while asking: “You wanted changes?” The police van brought him and about 20 others to a police precinct. They demanded ID and forced the detainees to lie on the floor. “They beat and kicked each of us, including our faces. It was probably at that moment that my nose was broken.”

Afterward, according to Kiryl, he and around 15 others were taken to the basement where they were required to lie down or kneel and sing the national anthem while being beaten. Then, they were taken to Akrestsina jail and placed in an outdoor yard. Later, he and around 35 others were packed into a stifling jail cell designed for perhaps seven or eight prisoners. He thought they were not offered food until the next day. Water wasn’t a problem; detainees drank from a common faucet. At around 2 a.m., they were all released. Despite his protests that he was in no way involved, Kiryl and the others were all required to sign a written warning about refraining from participation in future unsanctioned protests.

Kiryl said that during the entire time of his detention, his mother had no idea what had happened to him and was frantically searching hospitals and prisons.

“I see that I live in a country where it’s dangerous to even venture out from home to your place of employment. Anyone can be taken. I am more concerned about my relatives than about myself. They could disappear and nobody would know what happened to them.”

Three Stories From Vitsebsk

We spoke to people from the city of Vitsebsk who were detained near a polling station on August 9, election night. They were beaten and put behind bars. They spoke about physical pain and moral pressure, about being treated like criminals. They say they violated no law, but it was their rights that were violated.

“You feel like you are in a movie about life in a concentration camp.”

Maksim Zhukau, 45, is a businessman and civic activist. Zhukau said that at the polling station, he started to film as riot police were detaining people, accusing them of taking part in an unsanctioned protest. “Within a minute, I was in the police van,” Zhukau told us.

It was after midnight when they brought him to the jail cell. There were seven others there. “Almost all the cells are like saunas, with black mold in every corner. There’s a toilet in the center, with no partitions. Some were told to remove their shoes and wound up barefoot. There were no bed sheets. We were lying on metal plates. You start to ache after about 20 minutes.”

They were transported to another detention center the following day. “We were told to strip naked for the search and to crouch,” and then directed to a cell. “We were cursed and verbally abused nonstop.” That day, he was tried in the detention center and sentenced to 15 days for violating laws about unsanctioned protests.

“You are always forced to walk bent over, eyes down. You are shoved. You are wounded on a moral level. You feel like you are in a movie about life in a concentration camp. People are in a state of shock. You can’t make sense of any of it. I didn’t eat for almost four days.”

![]()

“It’s scary in the detention center. You’re in a closed space, among armed men, with trained dogs. They can do whatever they want with you, and no one will know about it."

“But we were lucky. Compared to Minsk, our [detention center] was like a five-star resort, in spite of the moral pressure.”

Zhukau was released after five days and filed a complaint for unlawful arrest. He believes it’s important to spread information about the brutalities of the security forces. “These people should be tried and put behind bars, some of them for life.”

“A normal person wouldn’t be capable of administering such beatings.”

Mikalay Kachurets, 61, is a driver. Despite his age, he was beaten, some of his hair was pulled out, and he was deprived of his daily hypertension and blood-thinning drugs.

Kachurets was detained on his way to a protest, and he was unfurling a flag. “They bundled me up and threw me into the police van. Inside, I had the feeling that they were trying to kill me, hitting me on the head with their fists. The blows were severe. It was obvious that they were professionally trained. Another cop started to tear my hair out. He hit me hard. A normal person wouldn’t be capable of administering such beatings. It’s barbaric, fascism. He was yelling and pulling my hair out with both hands.”

“My eye was cut, my nose was bleeding. They continued beating me. They all wore masks and had no badges.”

“They wouldn’t let us go to the bathroom. They were yelling as though we were animals. I was badly beaten. They provided no medical assistance."

![]()

For his evening walk, Mikalay was sentenced to 15 days in jail. He served five days before being released and filed a complaint.

“For the first few days, I recuperated in my [room]. I cried. More than anything, I was afraid that once I was released, I’d find out that everybody ran away and hid.”

“It resembled a kidnapping of some sort.”

Uladzimer, 31, is a musician, historian, and civic activist

He was badly beaten on election night, August 9. A doctor who examined him said the injuries were indicative of a criminal assault.

He was stopped, along with a group of friends, on their way to a protest rally. “A guy ran up to me from behind and started to hit me with his truncheon. I was on the ground. He pressed his knee into my bladder and I wet myself. Right after that, two of his colleagues rushed up, and all three of them continued to beat me with their truncheons.”

There was no room at many of the detention centers. “For hours, we drove all around the city. They kept transferring us from one police van to another. It resembled a kidnapping of some sort.”

Finally, they arrived at a detention center. “There were 33 of us, all men and one woman. They started to beat two of the guys in order to scare the rest of us. One guy had a prostate problem. They wouldn’t let him go to the bathroom. They just gave him a bottle. He had some sort of heart attack right there in the room. Until the ambulance arrived, they offered him no medical assistance. The rest of us stayed there on our knees, unable to move, constantly hit by truncheons."

Uladzimer was released at 3 a.m. the following morning, documented his injuries, and filed a complaint for a miscarriage of justice.

"They forced people to pray as they started to beat them."

Mikitar Tselizhenka is a correspondent for the Russian publication Znak.com. He was detained on the evening of August 10 in the center of Minsk, while writing an SMS on his phone. “They thought I was writing something on Telegram. They assumed that anybody tinkering with their phone is a protest coordinator,” Tselizhenka said.

"They brought me to the police precinct. Everyone there, without exception, was beaten. People were screaming [in pain], and some lost control [of their bladders].”

“All of this was happening in the calm presence of the other police officers, who are supposed to protect people. They forced people to pray as they started to beat them. ‘Say the Lord’s Prayer!’ And then they’d batter them with truncheons, their legs, and anything else. They hit them on the head, on the legs. They slammed one guy with full force against a door frame.”

“As soon as you walk in, you’re forced to the floor face first. If you move, you get hit. The guy next to me looked as though he had his teeth knocked out. For 16 hours, you’d be lying in that position. People were being beaten on two or three floors [of the jail], judging by the screams.”

“The following morning, we were taken downstairs where the cells are. They’re designed for two or three, but there were 20 to 30 people in each, with no ventilation. People are forbidden to sit down, forbidden to move, no matter their age or gender. People just stood and stewed. People were losing consciousness due to the lack of air. There were people there with injured backs, arms, legs, with concussions. No one got any medical attention.”

"The government has lost all respect."

Yury Sirash, the director of the intensive-care unit at Minsk Emergency Hospital, described the trauma and suffering endured by victims of riot police.

Sirash said ambulances weren’t allowed to enter areas where people were injured, riot police beat medical volunteers, and even attacked the injured. He talked about the terrible condition of people brought to the hospital from Akrestsina jail. He said he had lost all respect for the government.

![]()

"On August 11, emergency medical workers weren’t allowed access [to injured people in the streets]. Their teams could only deploy to protest sites if summoned by police. They weren’t allowed! That upset us greatly, because these are battle wounds. The sooner you provide medical aid, the greater the chances the victim will survive.”

“But we didn’t despair. Doctor-volunteers packed up their gear and Red Cross badges and went right out 'to the front.'”

“But then the next stage started, when they began to detain the medics as well, and take them to Akrestsina jail, doctors and nurses. The result was that the injured were left without medical care.”

“I suspect that many of the injured are now staying home. They’re afraid of further persecution by the authorities. And we’re going to have even more repercussions: complications from these injuries.”

Sirash explained that, according to international norms, Red Cross workers in war zones should not be prevented from doing their work by either side of a conflict.

“Volunteers spoke about how they were beaten by riot police -- volunteers wearing Red Cross badges!”

Sirash said one volunteer told him that when he explained to the riot police that he was providing medical aid, they hit him with truncheons and attacked the wounded man he was caring for.

Sirash said he and most of his colleagues had rarely, in their professional careers, encountered wounds of the kinds seen in wake of the protests.

The wounds of the detainees from Akrestsina jail “were horrifying to behold. You’d lift a T-shirt, and you’d see mottled flesh, all blue.” Victims would howl in pain when moved from a stretcher.

“Furthermore, they branded them with indelible paints of some kind, on the forehead and arm. Why? I don’t know."

“That’s what forced us to rise up. That was beyond the pale.”

“If we all go out and together say ‘No!’ then we are a force. Only together can we change the situation,” Sirash said. “The government has lost all respect. It doesn’t understand that once it has lost respect, the game is over."

29 August 2020, 00:34

RFE/RL's Belarus Service collected the testimonies of people who say they were victims of state-sanctioned violence on the streets and in the jails.

“We agreed to keep quiet to preserve enough air for everybody.”

Yana, a cultural worker, was detained while trying to come to the rescue of a friend. The police van they put her in was packed. She was taken to Akrestsina jail in Minsk and put into a tiny cell designed for six but filled with some 50 detainees. She was tried within the jail walls and got a four-day sentence.

“In my cell, there was an English-language teacher, a mother of five, a designer. We weren’t fed. You could drink from the faucet, but the water was undrinkable. We managed to avoid it for 24 hours but then started to drink. We tried to sleep as best as we could manage. There was no air. We agreed to keep quiet in order to preserve enough air for everybody [to breathe].”

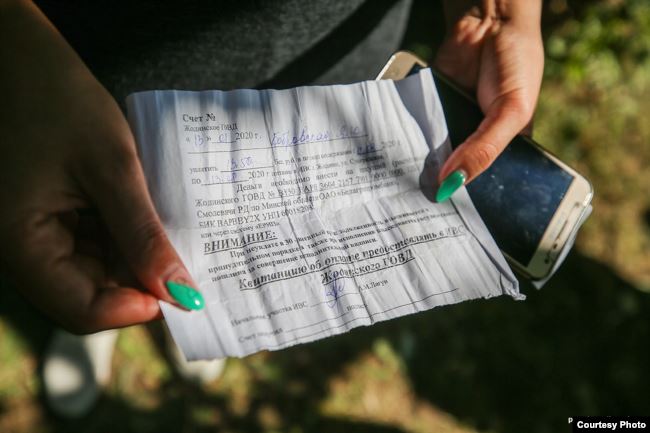

“The men were out for beatings, mostly at night, [perhaps] so no one would hear. But you could hear everything, even the [protest] supporters outside. Workers at the Zhodzina jail cried when we told them our stories [about Akrestsina]. There, we were fed for the first time in three days. Upon leaving, I was presented with a bill for the food given to us at Zhodzina jail.”

Yana shows the bill for the food given to her at Zhodzina jail.

“I was released on Thursday night and started to look for my things. We were told that those who came from 'Auschwitz' (Akrestsina jail) would find none of their belongings. There was a feeling that we were deprived of all our rights, that they could do with you whatever they pleased. On the third day, I became hysterical. I started to imagine that I would remain there forever.”

“I asked the police how to get home. In response, they started beating me.”

Hanna, a 30-year-old graphic designer, says she was heading home around midnight on August 11. There was a roadblock, so she asked some police officers how to get around it. They offered to escort her and also asked for identification. Instead of taking her home, they drove to a location where police vans were parked. Suddenly, she was thrown into one of them, and she said they started to beat her.

“They kicked me, beat me with truncheons, with one blow over the head. A large hematoma immediately bloomed on my forehead. They were screaming that I was a coordinator of the protests. They demanded that I admit it and tell them who was paying me. I said I didn’t know what they were talking about. For every response like that, I received another blow. It was the scariest night of my life.”

Hanna

Hanna recounts that she was then taken to a police precinct building where about 40 people were kept in a large room. Blood and vomit covered the floors. They threw her on the floor and threatened to cut off her dreadlocks. She was then taken to an interrogation room and questioned by seven police officers who kept asking her the same question: Who was financing her "subversive activity?” She said that every time she pleaded ignorance, she was struck with a truncheon below the waist. After that, she was taken into another large room with many people. A police officer came over and spray-painted a number on her shirt. She later found out that the number branded her as one of the protests' most active participants.

The next morning, she was transported to the Akrestsina jail. Lightly dressed in a T-shirt and shorts, she spent the night with two other women in a cold, roofless, cement cell. She says they could hear the screams and moans of men being beaten all night in nearby cells. The following day, she was placed in a cell designed for four, but packed with some 30 or 40 others. Some there hadn’t eaten for two days. One woman arrested with her husband pleaded desperately with the jailers to allow her to telephone her children, who had been left alone at home. On the third day after Hanna's detention, she was released and required to sign a written warning saying that if she were arrested again, she would face criminal charges.

“In the Partyzanski district Internal Affairs Department, we were forced to sing the Belarusian national anthem on our knees while being beaten with truncheons.”

Kiryl, a 21-year-old store clerk, said he was walking to work from a session at the gym on August 12. A bus with tinted windows pulled up and he was ordered to get in. His phone was taken, and he was struck on the head a few times. The bus pulled up to a police van, and he was thrown on the floor. A police officer started to kick him while asking: “You wanted changes?” The police van brought him and about 20 others to a police precinct. They demanded ID and forced the detainees to lie on the floor. “They beat and kicked each of us, including our faces. It was probably at that moment that my nose was broken.”

Kiryl

Afterward, according to Kiryl, he and around 15 others were taken to the basement where they were required to lie down or kneel and sing the national anthem while being beaten. Then, they were taken to Akrestsina jail and placed in an outdoor yard. Later, he and around 35 others were packed into a stifling jail cell designed for perhaps seven or eight prisoners. He thought they were not offered food until the next day. Water wasn’t a problem; detainees drank from a common faucet. At around 2 a.m., they were all released. Despite his protests that he was in no way involved, Kiryl and the others were all required to sign a written warning about refraining from participation in future unsanctioned protests.

Kiryl said that during the entire time of his detention, his mother had no idea what had happened to him and was frantically searching hospitals and prisons.

“I see that I live in a country where it’s dangerous to even venture out from home to your place of employment. Anyone can be taken. I am more concerned about my relatives than about myself. They could disappear and nobody would know what happened to them.”

Three Stories From Vitsebsk

We spoke to people from the city of Vitsebsk who were detained near a polling station on August 9, election night. They were beaten and put behind bars. They spoke about physical pain and moral pressure, about being treated like criminals. They say they violated no law, but it was their rights that were violated.

“You feel like you are in a movie about life in a concentration camp.”

Maksim Zhukau, 45, is a businessman and civic activist. Zhukau said that at the polling station, he started to film as riot police were detaining people, accusing them of taking part in an unsanctioned protest. “Within a minute, I was in the police van,” Zhukau told us.

Maksim Zhukau

It was after midnight when they brought him to the jail cell. There were seven others there. “Almost all the cells are like saunas, with black mold in every corner. There’s a toilet in the center, with no partitions. Some were told to remove their shoes and wound up barefoot. There were no bed sheets. We were lying on metal plates. You start to ache after about 20 minutes.”

They were transported to another detention center the following day. “We were told to strip naked for the search and to crouch,” and then directed to a cell. “We were cursed and verbally abused nonstop.” That day, he was tried in the detention center and sentenced to 15 days for violating laws about unsanctioned protests.

“You are always forced to walk bent over, eyes down. You are shoved. You are wounded on a moral level. You feel like you are in a movie about life in a concentration camp. People are in a state of shock. You can’t make sense of any of it. I didn’t eat for almost four days.”

Maksim Zhukau

“It’s scary in the detention center. You’re in a closed space, among armed men, with trained dogs. They can do whatever they want with you, and no one will know about it."

“But we were lucky. Compared to Minsk, our [detention center] was like a five-star resort, in spite of the moral pressure.”

Zhukau was released after five days and filed a complaint for unlawful arrest. He believes it’s important to spread information about the brutalities of the security forces. “These people should be tried and put behind bars, some of them for life.”

“A normal person wouldn’t be capable of administering such beatings.”

Mikalay Kachurets, 61, is a driver. Despite his age, he was beaten, some of his hair was pulled out, and he was deprived of his daily hypertension and blood-thinning drugs.

Mikalay Kachurets

Kachurets was detained on his way to a protest, and he was unfurling a flag. “They bundled me up and threw me into the police van. Inside, I had the feeling that they were trying to kill me, hitting me on the head with their fists. The blows were severe. It was obvious that they were professionally trained. Another cop started to tear my hair out. He hit me hard. A normal person wouldn’t be capable of administering such beatings. It’s barbaric, fascism. He was yelling and pulling my hair out with both hands.”

“My eye was cut, my nose was bleeding. They continued beating me. They all wore masks and had no badges.”

“They wouldn’t let us go to the bathroom. They were yelling as though we were animals. I was badly beaten. They provided no medical assistance."

Mikalay Kachurets

For his evening walk, Mikalay was sentenced to 15 days in jail. He served five days before being released and filed a complaint.

“For the first few days, I recuperated in my [room]. I cried. More than anything, I was afraid that once I was released, I’d find out that everybody ran away and hid.”

“It resembled a kidnapping of some sort.”

Uladzimer, 31, is a musician, historian, and civic activist

He was badly beaten on election night, August 9. A doctor who examined him said the injuries were indicative of a criminal assault.

He was stopped, along with a group of friends, on their way to a protest rally. “A guy ran up to me from behind and started to hit me with his truncheon. I was on the ground. He pressed his knee into my bladder and I wet myself. Right after that, two of his colleagues rushed up, and all three of them continued to beat me with their truncheons.”

Uladzimer

There was no room at many of the detention centers. “For hours, we drove all around the city. They kept transferring us from one police van to another. It resembled a kidnapping of some sort.”

Finally, they arrived at a detention center. “There were 33 of us, all men and one woman. They started to beat two of the guys in order to scare the rest of us. One guy had a prostate problem. They wouldn’t let him go to the bathroom. They just gave him a bottle. He had some sort of heart attack right there in the room. Until the ambulance arrived, they offered him no medical assistance. The rest of us stayed there on our knees, unable to move, constantly hit by truncheons."

Uladzimer was released at 3 a.m. the following morning, documented his injuries, and filed a complaint for a miscarriage of justice.

"They forced people to pray as they started to beat them."

Mikitar Tselizhenka is a correspondent for the Russian publication Znak.com. He was detained on the evening of August 10 in the center of Minsk, while writing an SMS on his phone. “They thought I was writing something on Telegram. They assumed that anybody tinkering with their phone is a protest coordinator,” Tselizhenka said.

"They brought me to the police precinct. Everyone there, without exception, was beaten. People were screaming [in pain], and some lost control [of their bladders].”

“All of this was happening in the calm presence of the other police officers, who are supposed to protect people. They forced people to pray as they started to beat them. ‘Say the Lord’s Prayer!’ And then they’d batter them with truncheons, their legs, and anything else. They hit them on the head, on the legs. They slammed one guy with full force against a door frame.”

“As soon as you walk in, you’re forced to the floor face first. If you move, you get hit. The guy next to me looked as though he had his teeth knocked out. For 16 hours, you’d be lying in that position. People were being beaten on two or three floors [of the jail], judging by the screams.”

“The following morning, we were taken downstairs where the cells are. They’re designed for two or three, but there were 20 to 30 people in each, with no ventilation. People are forbidden to sit down, forbidden to move, no matter their age or gender. People just stood and stewed. People were losing consciousness due to the lack of air. There were people there with injured backs, arms, legs, with concussions. No one got any medical attention.”

"The government has lost all respect."

Yury Sirash, the director of the intensive-care unit at Minsk Emergency Hospital, described the trauma and suffering endured by victims of riot police.

Sirash said ambulances weren’t allowed to enter areas where people were injured, riot police beat medical volunteers, and even attacked the injured. He talked about the terrible condition of people brought to the hospital from Akrestsina jail. He said he had lost all respect for the government.

Yury Sirash

"On August 11, emergency medical workers weren’t allowed access [to injured people in the streets]. Their teams could only deploy to protest sites if summoned by police. They weren’t allowed! That upset us greatly, because these are battle wounds. The sooner you provide medical aid, the greater the chances the victim will survive.”

“But we didn’t despair. Doctor-volunteers packed up their gear and Red Cross badges and went right out 'to the front.'”

“But then the next stage started, when they began to detain the medics as well, and take them to Akrestsina jail, doctors and nurses. The result was that the injured were left without medical care.”

“I suspect that many of the injured are now staying home. They’re afraid of further persecution by the authorities. And we’re going to have even more repercussions: complications from these injuries.”

Sirash explained that, according to international norms, Red Cross workers in war zones should not be prevented from doing their work by either side of a conflict.

“Volunteers spoke about how they were beaten by riot police -- volunteers wearing Red Cross badges!”

Sirash said one volunteer told him that when he explained to the riot police that he was providing medical aid, they hit him with truncheons and attacked the wounded man he was caring for.

Sirash said he and most of his colleagues had rarely, in their professional careers, encountered wounds of the kinds seen in wake of the protests.

The wounds of the detainees from Akrestsina jail “were horrifying to behold. You’d lift a T-shirt, and you’d see mottled flesh, all blue.” Victims would howl in pain when moved from a stretcher.

“Furthermore, they branded them with indelible paints of some kind, on the forehead and arm. Why? I don’t know."

“That’s what forced us to rise up. That was beyond the pale.”

“If we all go out and together say ‘No!’ then we are a force. Only together can we change the situation,” Sirash said. “The government has lost all respect. It doesn’t understand that once it has lost respect, the game is over."